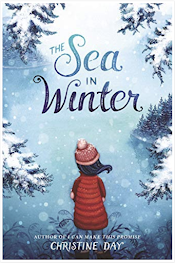

By Christine Day (Upper Skagit)

Back in September 2020, Debbie blogged about her positive reaction to reading the ARC of Christine Day's second novel for young people -- The Sea in Winter. Since then, the book has gotten positive critical attention, including a Kirkus starred review and School Library Journal "Best Book". Here, finally, is my "short and sweet" AICL review.

The publisher, Heartdrum, says this about The Sea in Winter:

It’s been a hard year for Maisie Cannon, ever since she hurt her leg and could not keep up with her ballet training and auditions. Her blended family is loving and supportive, but Maisie knows that they just can’t understand how hopeless she feels.... Maisie is not excited for their family midwinter road trip along the coast, near the Makah community where her mother grew up. But soon, Maisie’s anxieties and dark moods start to hurt as much as the pain in her knee. How can she keep pretending to be strong when on the inside she feels as roiling and cold as the ocean?

Reason One to recommend The Sea in Winter: The sense of place.

The author writes from the heart when she describes the story's setting. It's good to have a book about a contemporary middle schooler, that celebrates geoduck clams and the removal of the Elwha River dam. It's set in much the same part of the continent as a certain popular vampire-and-werewolf series, but Day's storytelling is noticeably more attuned to the landforms, the weather, the animals, the sea.

Reason Two: Respect for advocacy and activism.

Advocacy for social and environmental justice, and for Indigenous rights, are natural parts of family life in Maisie's world. For example, readers learn that her family has been directly affected by treaty rights to harvest shellfish, and removal of dams that kept salmon from spawning in local rivers. And conflict around the 1999 Makah whale hunt (the tribe's first effort to hold its traditional hunt in 70 years) forced an important decision for some of Maisie's Makah relatives.

Reason Three: The protagonist's unique perspective.

The Sea in Winter offers the young reader a window on the experience of a child with an unusual level of ambition. Most children Maisie's age haven't discovered an activity that inspires the kind of commitment she has to ballet. What is it like, at age 12, to have your entire life, including peer friendships, revolve around ballet, because you love it that much? Who else understands such dedication? And how do you cope, at age 12, when you face the loss of your beautiful dream? Is that what depression feels like?

Reason Four: Maisie's solid, loving Native family.

Leo Tolstoy famously, or infamously, wrote, "All happy families are alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way." Though Maisie's family faces some challenges, including Maisie's depression, they are fundamentally "happy" together -- affectionate, thoughtful, supportive, respectful of boundaries, and knowledgeable about their Native identities. But they're by no means ordinary, stereotypical, or indistinguishable from other fictional families that are doing essentially okay. The author makes them interesting, not merely quirky or weird, as individuals and as a unit.

In short, I add my voice to the chorus of recommendations: Read and share The Sea in Winter with young people in your life!